Admin

Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorPosts

-

AdminKeymaster

AdminKeymasterPatients are the centre of the healthcare services so they must have a voice in Patient Safety. The WHO programme Patients for Patient Safety aims to engage patients as partners, using the patient experience as a learning tool and promoting patients’ leadership and involvement towards safer care.1

Please find more here: https://www.who.int/initiatives/patients-for-patient-safety

The WHO Global Safety Action Plan 2021-2030 Strategic Objective 4 – Patient and family engagement sets a number of actions to engage and empower patient and families to help and support the journey to safer healthcare.2

- World Health Organization. Patients for patient safety: partnerships for safer health care [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44189

- Organization WH. Global Patient Safety Action Plan 2021-2030 Towards eliminating avoidable harm in health care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021.

AdminKeymaster

AdminKeymaster- The second victim phenomenon has profound consequences to the healthcare workers wealth and well-being.

- The second victim phenomenon is a matter of quality of care and a wide approach is crucial to tackle this problem.

To break the vicious cycle created by the occurrence of adverse events that undermines Patient Safety please consult the Recommendations for providing an appropriate response when patients experience an adverse event with support for healthcare’s second and third victims. (attachment)

This resource provides a comprehensive approach, with checklists for actions regarding patient safety, and the care and protection of all the victims involved, including of course, the second victims.

- The second victims need help, not punishment.

Peer-support programs seem to be the preferred way to support the second victims. We invite you to download the Peer Support Program Implementation Guide, a tool prepared to support your institution to deploy a peer-support program. (attachment)

AdminKeymaster

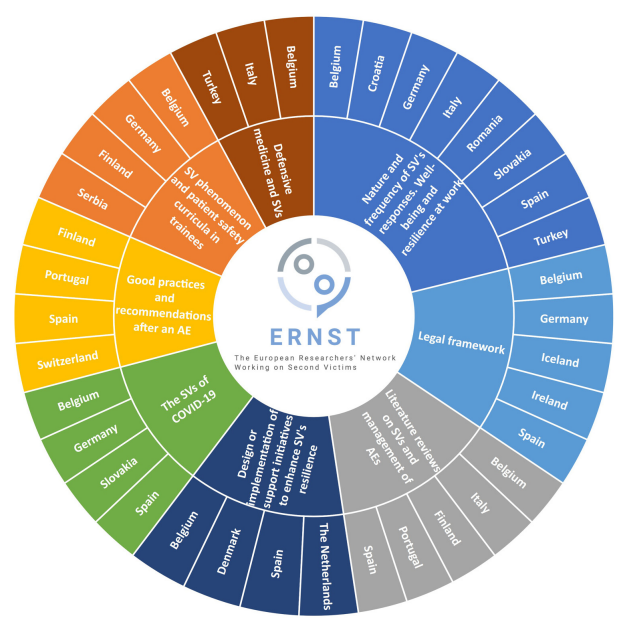

AdminKeymasterERNST Consortium has conducted a study to explore what supportive interventions are being implemented in Europe to enhance the resilience of healthcare professionals in stressful situations.

Through a cross-sectional study 1 an online survey was conducted in 82 academics and clinicians who had formalized their membership in the COST Action 19113 and members formally to ERNST by September 2020, represented 27 European and one neighbouring country. The study period was from September 25 to December 15, 2020.

The survey explored the scientific profile of the participants, their interests, experiences in the topic, challenges, gaps, and related areas of second victims. In this study was conducted to know what, how, and where studies and interventions were being conducted in Europe in this issue.

Results:

- A total of 70 members answered, 97.1% from European countries, these were Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Lithuania, Malta, Moldova, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey and 2.9% from a neighbour country this is Azerbaijan.

- The 60.7% of participants reported the existence of patient safety standards that incorporate some form of care for professionals who experience the second victim symptoms.

- The 37.1% of researchers involved in this COST Action were conducting studies or research underway on second victims or related issues (15 countries):

Main topics of the phenomenon of second victims studied by members of the European ERNST consortium and related research teams.. From Carrillo I, Tella S, Strametz R. Studies on the second victim phenomenon and other related topics in the pan-European environment : The experience of ERNST Consortium members. J Patient Saf Risk Manag. 2022;1–7 - 30% of the participants were involved in the design of interventions aimed at addressing the second victim phenomenon.

- At the time of this survey the 42.9% of participants were participating in the implementation in health centers of any intervention aimed at addressing the second victim phenomenon.

1. Carrillo I, Tella S, Strametz R. Studies on the second victim phenomenon and other related topics in the pan-European environment : The experience of ERNST Consortium members. J Patient Saf Risk Manag. 2022;1–7.

AdminKeymaster

AdminKeymasterThe care of second victims responds to the following objectives:

- It must be considered that when an adverse event occurs the professional doubts his or her capacity for clinical judgement. It is therefore necessary to adopt measures to ensure the quality of health care, considering that a premise for guaranteeing quality is that professionals feel that they have sufficient capacity to carry out their work in an appropriate environment. A supportive environment, a supportive organisation and an integrated team of professionals are prerequisites for providing optimal care.

- Minimise the negative emotional impact on second victims of unexpected incidents such as adverse events by providing them with the necessary support, which has a positive impact on safety of the following patients to be cared.

- Avoiding non-quality costs, since the individual and social effort involved in training a healthcare professional(s) is cut short when the professional doubts his or her clinical judgement and ability to continue in his or her profession and decides to leave or change position. The feeling of lack of protection reduces the quality of care, causes disaffection among professionals and, in short, makes it difficult, if not impossible provide optimal care. But this approach requires a non-punitive environment were talking about what happened does not have additional negative consequences.

Second Victim Experience and Support Tool (SVEST)

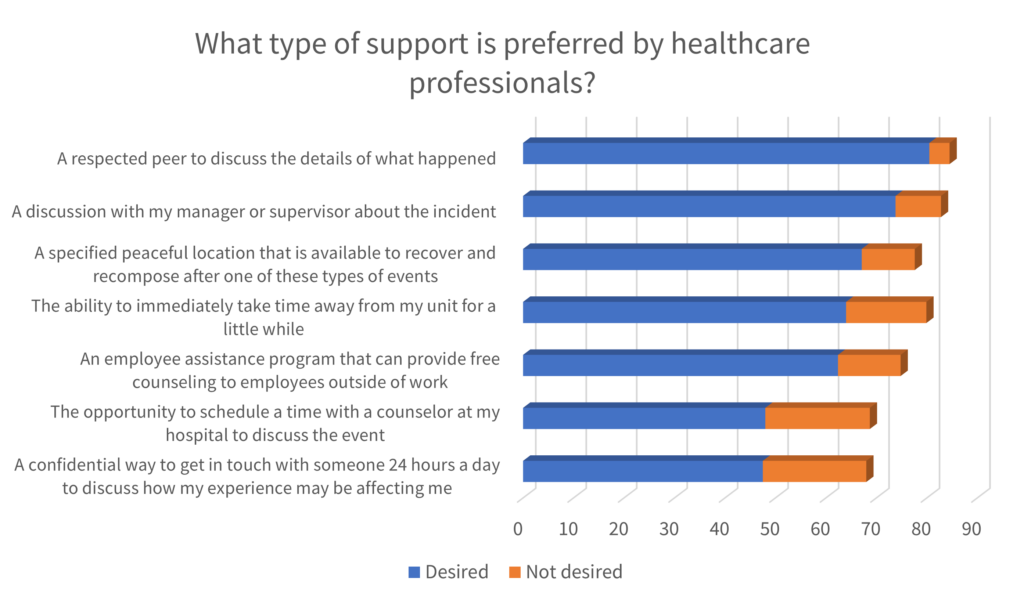

The Second Victim Experience and Support Tool (SVEST) was been created to better understand the needs of the second victims and to assist the implementation of support resources by the institutions.1 It was created and validated in the United States but currently it is also available in other languages.

Using this tool, Burlison et al1 found that the majority of the healthcare workers surveyed would prefer to have a “respected peer to discuss the details of what happened” when asked about the desirability of 7 support options.

Adapted and translated from Burlison, J.D., Scott, S.D., Browne, E.K., Thompson, S.G., & Hoffman, 2017 Accordingly, the peer support is the basis of several interventions directed to the second victims.

Peer Support

Peer Support is “emotional first aid” for healthcare providers who are involved in unanticipated adverse patient events, medical errors, or other stressful situations encountered through patient care. Providers involved in such events are often referred to as Second Victims, as they suffer significant emotional, physical, cognitive, and behavioural sequelae in the aftermath of such events. Peer Support is an effective tool in helping staff successfully manage difficult situations, increase resiliency, and decrease burnout.

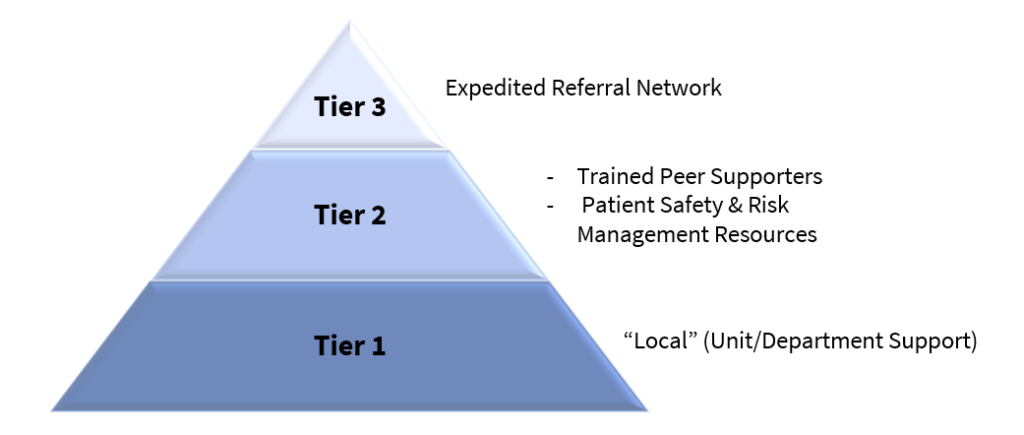

The three-stage intervention model suggested by Susan Scott2 is the most widespread framework to guide the support of second victims. It is based on peer support, first from the unit itself (basic emotional first aid) and at a second level by trained peers. The third level is based on more specialised support.

In most cases, the tier 1 will provide sufficient support to the victims; it is composed by peers and unit leaders that should have received some basic awareness training to the second victim’s needs. When necessary, the second victims can be referred for Tier 2, where specially trained peers can provide guidance and support. When the needs of the second victims exceeds the expertise of the peer supporters, they can be referred for Tier 3, composed by professional counsellors.

Adapted from Scott, 2010 In the ERNST Course, different programs to support the second victims are detailed: https://course.cost-ernst.eu/

Improving healthcare workers’ resilience

To protect healthcare workers from becoming second victims it is crucial to increase their resilience, that is the ability of individuals to withstand the stressful situation. 3

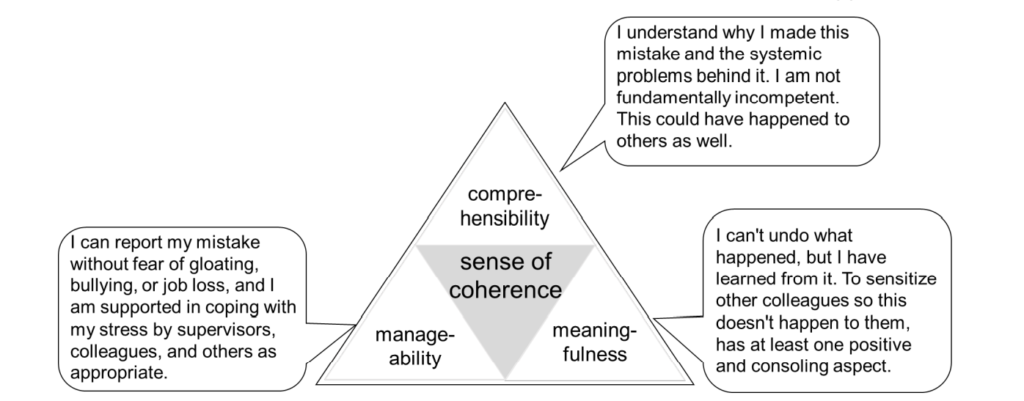

The sociologist Antonovsky described the sense of coherence, which is central to successfully coping with challenges, as a prerequisite for resilience.

The sense of coherence is composed of three domains. When confronted with a stressor, the person with a strong sense of coherence will:

- wish to, be motivated to, cope – meaningfulness.

- believe that the challenge is understood – comprehensibility.

- believe that resources to cope are available – manageability.

In the context of a healthcare environment where a worker was involved in an incident, the sense of coherence theory could be exemplified by the following statements. They illustrate the attitudes of resilient workers:

Translated from: Strametz R, Walcher F: [Perspectives of psychosocial support of HCW] in: [Healthworker Safety is Patient Safety – Psychosocial Support of HCW in Hospitals], (German), Kohlhammer: Stuttgart/Germany 2021 In terms of organisational support, the following measures should be considered3:

aspect of SoC organisational support measures to achieve this goal comprehensibility guaranteed systematic follow-up of the event with objective complete clarification of the facts of the case qualification of clinical risk managers to facilitate root-cause-analysis, including the appropriate provision of resourcesinitiation of root-cause-analysis for every second victim problem as part of the risk management strategy manageability Allow coming to rest enable reporting of the case and complaints in blame-free atmosphere support in coping with the situation as needed offer interruption of clinical activityestablishes a Just Culture to avoid gossip, bullying, or exclusion. sensitization of staff regarding the rapid recognition of possible second victim problems establishment of appropriate structures for the confidential support of a second victim by experts, if necessary meaningfulness recognition of the knowledge gained from the error and visibility of the systematic measures derived from it involvement in the analysis of this case and feedback to prevent future incidents and feedback on derived new preventive measures. establishment of a safety culture that deals constructively and explicitly with mistakes to learn from them The COVID-19 pandemic represented a major challenge for everyone. In particular, healthcare workers were exposed to high levels of work, physical exhaustion, emotional stress, and so on. Has become visible the need of caring for those who care.

A set of recommendations were designed, based on Scott’s model and SoC theory. 3 They aim to support the healthcare workers, increasing their resilience and helping to minimize the risk of overwhelming the healthcare system.

Please consult Recommendations: Maintaining capacity in the healthcare system during the COVID‐19 pandemic by reinforcing clinicians’ resilience and supporting second victims

- Burlison, J.D., Scott, S.D., Browne, E.K., Thompson, S.G., & Hoffman JM. The second victim experience and support tool (SVEST): Validation of an organizational resource for assessing second victim effects and the quality of support resources. J Patient Saf. 2017;13(2):93–102.

- SCOTT, Susan D. et al. – Caring for our own: Deploying a systemwide second victim rapid response team. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. . ISSN 15537250. 36:5 (2010) 233–240. doi: 10.1016/S1553-7250(10)36038-7.

- Strametz R, Raspe M, Ettl B, Huf W, Pitz A. Recommendations: Maintaining capacity in the healthcare system during the COVID‐19 pandemic by reinforcing clinicians’ resilience and supporting second victims. German Coalition for Patient Safety, Austrian Network for Patient Safety; 2020.

AdminKeymaster

AdminKeymasterBusch et al1 conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to quantify the negative impacts of adverse events on the providers involved. The most prevalent symptoms found were:

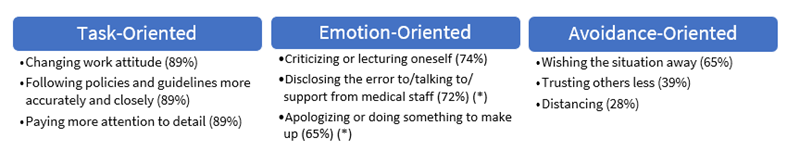

In another study, the same authors also have identified the coping strategies that are applied by the second victims.2 They divided the strategies found into task-oriented, emotion-oriented and avoidance-oriented; the former includes the most frequent strategies found, and the later includes the least-frequently used strategies. Some examples are presented below:

Second victims’ coping strategies – examples and frequency. (*) – strategy both task oriented and emotion oriented. Adapted from Busch IM, Moretti F, Purgato M, Barbui C, Wu AW, Rimondini M. Dealing With Adverse Events : A Meta-analysis on Second Victims ’ Coping Strategies. J Patient Saf. 2020;16(2):51–60. Stages of recovery

In a qualitative exploratory study Scott et al 3 identified the stages of the history of recovery of a second victim. A second victim could pass by the first three stages simultaneously:

Stage 1: Chaos and intrusive response Realization about what had occurred

Frequently distracted in self-reflection while trying to manage a patient in crisisHow did that happen?

Why did that happen?Stage 2: Intrusive reflections Re-evaluate scenario

Feelings of internal inadequacy and periods of self-isolationWhat did I miss?

Could this have been prevented?Stage 3: Restoring personal integrity Seeking support of a trusty individual (colleague, family, etc)

Managing gossipFear is prevalentWhat will others think?

Will I ever be trusted again?

How much trouble am I in?

How come I can’t concentrate?Stage 4: Enduring the inquisition Realization of level of seriousness

Respond to multiple ‘‘why’s’’ about the event

Understanding event disclosure to patient/family

Physical and psychosocial symptomsHow do I document?

Who can I talk to?

What happens next?

Will I lose my job/license?

How much trouble am I in?Stage 5: Obtaining emotional first aid Seek personal/professional support

Getting/receiving help/support

Litigation concerns emergeWhy did I respond in this manner?

What is wrong with me?

Do I need help?

Where can I turn for help?Stage 6: Moving on (one of three trajectories chosen) Dropping out: Transfer to a different unit, considering quitting, feelings of inadequacy Is this the profession I should be in?

Can I handle this kind of work?Surviving: Coping, but still have intrusive thoughts

Persistent sadness, trying to learn from eventHow could I have prevented this from happening?

Why do I still feel so badly/guilty?Thriving Maintain life/work balance

Gain insight/perspective

Does not base practice/work on one event

Advocates for patient safety initiativesWhat can I do to improve our patient safety?

What can I learn from this?

What can I do to make it better?The trajectory of recovery for the second victims. Adapted from Scott SD, Hirschinger LE, Cox KR, McCoig M, Brandt J, Hall LW. The natural history of recovery for the healthcare provider “second victim” after adverse patient events. Qual Saf Heal Care. 2009;18:325–30. Three potential results were described – dropping out, surviving, and thriving -, representing different experiences and career outcomes to the healthcare workers.

In another study4, second victim distress has been associated with absenteeism and turnover intentions. It was found that the organizational support may result in a decrease of second victim’s distress, mediating the relationships between distress-absenteeism and distress-turnover intentions. Thus, the healthcare organizations could have an important role in the outcomes of a second victim experience and should take care of the caregiver.

A second victim need:

- Talk about what happened. Understand why it happened.

- Know what to say and who to talk to.

- Not feel rejected by colleagues, and bosses.

- Emotional rest, cannot continue his/her work that same day.

- Feeling useful helps the mistake never happens again.

- Legal advice.

- Information about the incident investigation.

A second victim DO NOT need:

- To face a blaming attitude and rejection by colleagues and bosses.

- To be a target of rumors.

- Advices to not to talk about the incident and to not to notify.

- To feel that the emotional needs are ignored.

- To feel isolated.

- To be subject of repeated interrogations.

- Busch IM, Moretti F, Purgato M, Barbui C, Wu AW, Rimondini M. Psychological and Psychosomatic Symptoms of Second Victims of Adverse Events: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Patient Saf. 2020;16(2):E61–74.

- Busch IM, Moretti F, Purgato M, Barbui C, Wu AW, Rimondini M. Dealing With Adverse Events : A Meta-analysis on Second Victims ’ Coping Strategies. J Patient Saf. 2020;16(2):51–60.

- Scott SD, Hirschinger LE, Cox KR, McCoig M, Brandt J, Hall LW. The natural history of recovery for the healthcare provider “second victim” after adverse patient events. Qual Saf Heal Care. 2009;18:325–30.

- Burlison JD, Quillivan RR, Scott SD, Johnson S, Hoffman JM. The Effects of the Second Victim Phenomenon on Work-Related Outcomes: Connecting Self-reported Caregiver Distress to Turnover Intentions and Absenteeism. J Patient Saf. 2021;17(3):195–9.

AdminKeymaster

AdminKeymasterThe evidence shows that many healthcare workers have been involved in avoidable adverse events. Studies of the frequency of healthcare provider errors underline that more than 86% of healthcare professionals recognize an unintentional clinical error during their professional career, and 58% of them have reported serious adverse events.

- 92% surveyed physicians had been involved with a near miss, minor error, or serious error. 1

- 84% anaesthesiologists had been involved in at least 1 unanticipated death or serious injury over their career. 2

- 77% primary care professionals involved in safety incidents. (Newman 1996)

- 40% of physicians and nurses reported to have contributed to a severe adverse event in the last five years. (Mira et al 2016)

- 34% residents reported at least 1 major medical error between 2003 and 2005.3

- 14% physicians and 7.9% nurses reported to have contributed to a patient safety incident.4

From those who were involved in an incident, some will experience symptoms and become second victims. Common reactions can be emotional, cognitive, and behavioural. 5 As being a recent field of research, several studies tried to identify how many healthcare professionals become second victims. The following table summarizes some findings:

Author DAte location setting finding observations Dumitrescu A 2014 Ireland Department of Neonatology 92% Doctors and nurses. An I got Burnt Once (IGBO) – near-miss or actual clinical event, related to patient safety, that leaves a lasting impact on the health professional O’Beirne M 2012 Canada Primary care 82% Based on an incident reporting system. More frequent responses: frustration, embarrassment, anger and guilty Mira JJ 2015 Spain Primary care and hospitals 62% PC

72% HospDoctors and nurses. Reported having suffered the second-victim experience (themselves or through colleagues) in the previous 5 years Edrees H 2011 United States Tertiary care (hospital) 60% Can recall an adverse event in which they were a second victim Edrees H 2016 United States Department of Paediatrics 58% Experienced some problems, such as anxiety, depression, or concern about ability to perform job Seys D 2013 United States – 10-43% Systematic review The second victim phenomenon was also described on crisis situations as SARS pandemic in 2003. Tam and colleagues found that more than 50% of frontline healthcare workers had experienced psychological distress.6 More recently, the COVID-19 pandemic caused an unprecedent pressure on the healthcare systems and on the workers as well. 7 It was underlined that to respond to a crisis it is also crucial to take care of the healthcare workers wellbeing, who can easily become second victims in such stressful situations.

Van Slambrouck et. al found an 85% prevalence of second victim symptoms among nursing students, showing the importance of adequate education and training for the clinical experience. 8 In Germany, a survey of young physicians in training for internal medicine found that 59% of the respondents had already experienced second victim incidents in their career. 9

Gender-related differences should be addressed when tackling this problem: female workers tend to report more distress than male, but they are also more motivated to handle with the situation, discussing with colleagues and attending training programs. 5

- Waterman AD, Garbutt J, Hazel E, Dunagan WC, Levinson W, Fraser VJ, et al. The emotional impact of medical errors on practicing physicians in the United States and Canada. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33(8):467–76.

- Gazoni FM, Amato PE, Malik ZM, Durieux ME. The impact of perioperative catastrophes on anesthesiologists: Results of a national survey. Anesth Analg. 2012;114:596–603.

- West CP, Huschka MM, Novotny PJ, Sloan JA, Kolars JC, Habermann TM, et al. Association of perceived medical errors with resident distress and empathy: A prospective longitudinal study. J Am Med Assoc. 2006;296(9):1071–8.

- Van Gerven E, Vander Elst T, Vandenbroeck S, Dierickx S, Euwema M, Sermeus W, et al. Increased risk of burnout for physicians and nurses involved in a patient safety incident. Med Care. 2016;54(10):937–43.

- Seys D, Wu AW, Gerven E Van, Vleugels A, Euwema M, Panella M, et al. Health Care Professionals as Second Victims after Adverse Events: A Systematic Review. Eval Heal Prof. 2012;36(2):135–62.

- Tam CWC, Pang EPF, Lam LCW, Chiu HFK. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Hongkong in 2003: Stress and psychological impact among frontline healthcare workers. Psychol Med. 2004;34:1197–204.

- Wu AW, Connors C, Everly GS. COVID-19: Peer support and crisis communication strategies to promote institutional resilience. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(12):822–3.

- Van Slambrouck L, Verschueren R, Seys D, Bruyneel L, Panella M, Vanhaecht K. Second victims among baccalaureate nursing students in the aftermath of a patient safety incident: An exploratory cross-sectional study. J Prof Nurs [Internet]. 2021;37(4):765–70. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2021.04.010

- Strametz R, Koch P, Vogelgesang A, Burbridge A, Rösner H, Abloescher M, et al. Prevalence of second victims , risk factors and support strategies among young German physicians in internal medicine ( SeViD-I survey ). 2021;8:1–11.

AdminKeymaster

AdminKeymasterThe term “second victim” was first introduced by Dr Albert Wu.1 The author described the impacts of errors and mistakes on doctors and argued that little attention had being given on physician’s welfare and on how to handle to this problem. So, for the suffering and the need for help, doctors should be considered second victims of any medical error.

In the next years, the subject gained the attention of the researchers and a growing body of evidence was collected. In 2009, Scott et. al 2 proposed a comprehensive definition, comprising every healthcare worker and a broader range of causes of trauma. Second victims were defined as healthcare providers who are involved in an unanticipated adverse patient event, in a medical error and/or a patient related injury and become victimized in the sense that the provider is traumatized by the event. Frequently, these individuals feel personally responsible for the patient outcome. Many feel as though they have failed the patient, second guessing their clinical skills and knowledge base. 2

A new definition

In 2020, the European Researchers’ Network Working on Second Victims (ERNST) was established by the European Cooperation in Science and Technology (COST) as COST Action 19113.

One of the core objectives was to develop the theoretical conceptualization of the second victim phenomenon and to develop a common understanding of its definition. It was considered that the current definitions of Wu (2000) and Scott and colleagues (2009), mentioned before, are in some cases unclear. Also, they were both developed in the United States and did not include current insights.

A systematic review of the literature was performed, followed by a series of meetings and a final expert consensus.

A new definition was proposed based on three concepts :

- involved persons

- content of action

- impact

Here’s the proposed definition:

“Any health care worker, directly or indirectly involved in an unanticipated adverse patient event, unintentional healthcare error, or patient injury and who becomes victimized in the sense that they are also negatively impacted.”3

- Wu AW. Medical error: The second victim. BMJ. 2000;320:726–7.

- Scott SD, Hirschinger LE, Cox KR, McCoig M, Brandt J, Hall LW. The natural history of recovery for the healthcare provider “second victim” after adverse patient events. Qual Saf Heal Care. 2009;18:325–30

- Vanhaecht, K., Seys, D., Russotto, S., Strametz, R., Mira, J., Sigurgeirsdóttir, S., Wu, A. W., Põlluste, K., Popovici, D. G., Sfetcu, R., Kurt, S., & Panella, M. (2022). An Evidence and Consensus-Based Definition of Second Victim: A Strategic Topic in Healthcare Quality, Patient Safety, Person-Centeredness and Human Resource Management. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(24), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416869

September 13, 2022 at 11:05 am in reply to: Protecting the reputation of health professionals and the organization #1057 AdminKeymaster

AdminKeymaster- Review the communication plan in the light of experience, to ensure that in the months following the incident positive news about the care work are disseminated, to help to generate trust in the centre and its staff among the public.

- Regularly update information on new interventions in the field of clinical safety underway in the centre.

- Disseminate news on the therapeutic achievements and training activities carried out, to help strengthen confidence of patients, and the public in general, in the organization and its staff.

AdminKeymaster

AdminKeymaster- Ensure that there is a suitable place to talk with the patient and/or his/her family members without interruptions.

- With the available information well organized, arrange for a senior medical practitioner (it is not always a good idea that the health professional involved in the 2 incident informs the patient), together with another health professional known to the patient (or his/her family) to provide honest information to the patient, and show empathy with their suffering, including making an apology. If various patients are involved, the information should be provided privately to each one. In some cases, the health professional involved, if willing and capable of doing so, may participate in this meeting to inform the patient (though never on their own).

- Consider setting up an information team depending on the characteristics and magnitude of the adverse event.

- Ensure that the communication does not intimidate the patient. The amount of information given the frequency and the number of professionals who inform should be carefully controlled.

- Place importance on supplying information fast, even though it may initially be incomplete, making patients aware of this limitation.

- Assess whether there are intrinsic patient related factors (personality, emotional situation, etc.) that weigh against informing the patient directly. This will occur in isolated cases. Assess what the patient(s) and family members know and what they want to know.

- Decide, by consensus between a team of professionals, what information is to be given, in what order, and how to apologise with empathy. Confine the discussion strictly to facts and objective data.

- Do not make judgements about causality or responsibility, confining the conversation to what is known about the incident and objective clinical data. Avoid speculation. Do not use jargon or words that the patient does not understand. As a rule, avoid terms that could be confusing or have legal implications that go beyond the goal of providing honest information to the patient. In relation to this, it is not recommended to use terms such as error or mistake; rather explain that the outcome has been unexpected. The way this process is carried out should reflect the fact that most adverse events have systemic causes, which are not directly attributable to a specific health professional.

- Strive to reduce uncertainty without entering detailed analysis. Pay attention to nonverbal communication, ensuring that the patient and family members feel that the concern and respect shown by the health professional are genuine. Health professionals should talk to each other about the adverse event before informing the patient to reduce the emotional stress and create a climate of trust among healthcare team members.

- Meet any special needs of the patient in terms of communication, considering their age, family situation, and language in which they are most comfortable, among other factors.

- Record the meeting for informing the patient and/or family members if they give their consent. In such cases, a copy must be made available to the patient on request.

- Check whether the patient will or would like to be accompanied by a family member, in the case of patients under 18 years of age.

- Request written consent from the patient to share information with specialists in other centres or health services, as appropriate. In such cases, do not supply the name of the patient or other personal details, sharing only the minimum necessary information with third parties.

- Have and make available information a legal advice about when and how to proceed with an asset of financial compensation.

- Inform the patient and/or family not only about the incident but also about the steps being taken to determine what happened and how to prevent similar events in the future.

- Make sure that the patient and/or family members understand the information given and that they do not have any outstanding queries.

- Keep a line of communication open between the patient and the contact health professional. Update the information regarding the incident as more details become available.

- Make a note in the patient’s medical record specifying the information given to the patient/family with details of their questions and level of understanding of the information.

- Plan follow-up to support the patient through the course of their illness and with paperwork, in such cases.

- When needed, offer to the patient the option of changing his/her healthcare team.

Other resources – Open Disclosure:

- Open Disclosure Handbook: Clinical Excellence Commission. Open disclosure Handbook. Sidney: Clinical Excellence Commission; 2014.

- Canadian Guidelines: Disclosure Working Group. Canadian disclosure guidelines: being open and honest with patients and families. Edmonton, AB: Canadian Patient Safety Institute; 2011.

- Australian Open Disclosure Framework Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Australian Open Disclosure Framework. Sidney: ACSQHC; 2013.

September 13, 2022 at 11:01 am in reply to: Recommendations for detailed analysis of the incident #1052 AdminKeymaster

AdminKeymaster- Ensure that information is reported in an appropriate context and through an appropriate medium addressing all questions as openly and honestly as possible as they arise.

- Activate the team responsible for conducting the root cause analysis (as appropriate).

Suggested bibliography: How to perform a root cause analysis for workup and future prevention of medical errors – a review: Charles R, Hood B, Derosier JM, Gosbee JW, Li Y, Caird MS, et al. How to perform a root cause analysis for workup and future prevention of medical errors: A review. Patient Saf Surg [Internet]. 2016;10(1):1–5. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s13037-016-0107-8

- Arrange a meeting of the Safety Committee to analyse the results of the case analysis or root cause analysis (as appropriate) and propose measures to increase patient safety.

- Establish the information required and a deadline for reporting it, minimising delays.

- Decide whether it is appropriate to invite representatives of registered patient associations to participate in the case analysis or root cause analysis (as appropriate).

- When needed, inform the patient who has experienced the adverse event (or his/her family) of the results of the analysis. This could be useful in some cases.

- Introduce measures to increase patient safety and assess their effectiveness.

- With the appropriate confidentiality, hold clinical sessions to discuss medical errors and how to decrease the risk of them occurring in the future.

- Reflecting on the experience of an adverse event, review procedures for ensuring that personal information disclosed about patients and health professionals after an adverse event with media impact respect their rights to confidentiality and personal privacy. Consider that once agreement has been reached on measures to improve procedures and avoid adverse events due to a similar cause in the future, it is not relevant or necessary to provide further information, remembering also that relevant information has been noted in the patient’s medical record.

AdminKeymaster

AdminKeymasterEducation and training could be used to enhance speaking-up behaviour. If it includes the whole team that would provide an opportunity to build shared understanding about everyone’s perspectives and to improve the communication and ultimately, the confidence to speak-up. 1

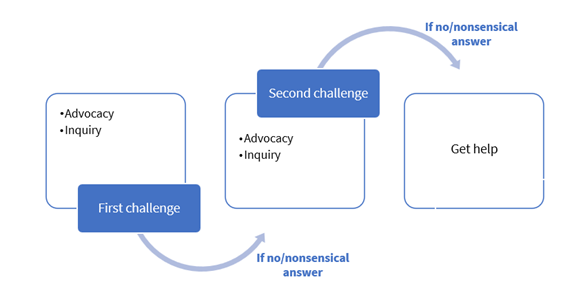

Two-Challenge Rule

Two-Challenge Rule has roots in aviation industry. One team member assumes the responsibility of the duties of another team member when it fails to respond to two consecutive challenges. In aviation case, both pilots have the same skills and can perform the same duties.Healthcare settings are different because of hierarchic gradients and differences in skills between team members – e.g., a nurse won’t be able to substitute a surgeon during a procedure. Still, two-challenge rule can be applied by calling for external assistance.

Pian-Smith et. al 2 suggested to pair advocacy and inquiry when applying this rule in healthcare settings. It starts to a statement describing an opinion followed by a question aiming to request que other person thoughts. Example: “I see that you plan to administer a spinal anaesthetic to this patient. She has a platelet count of 80,000. I learned that we shouldn’t do a spinal unless the count was at least 100,000. Can you clarify your view?”.

If no answer or a nonsensical answer, another advocacy-inquiry pair should be applied, and if no answer or nonsensical answer again, additional help should be sought.

Two-Challenge Rule. From Pian-Smith MCM, Simon R, Minehart RD, Podraza M, Rudolph J, Walzer T, et al. Teaching residents the two-challenge rule: A simulation-based approach to improve education and patient safety. Simul Healthc. 2009;4(2):84–91. Graded Assertiveness

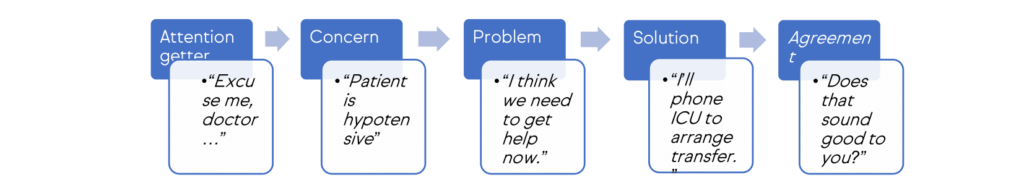

Graded assertiveness is a technique to improve communication when facing unsafe practice. It empowers the worker to use a structured, diplomatic, and respectful communication, preventing initial confrontation, when trying to redirect the management of the situation. It gives space to the other professional to correct any mistake/misunderstanding. When the achieved outcome is reached, the communication returns to the normal, but if necessary, it can progress to the next level with gradual increase in confidence.3It is particularly valuable for junior workers/interns to express their concerns in an appropriate and non-confrontational manner. 3

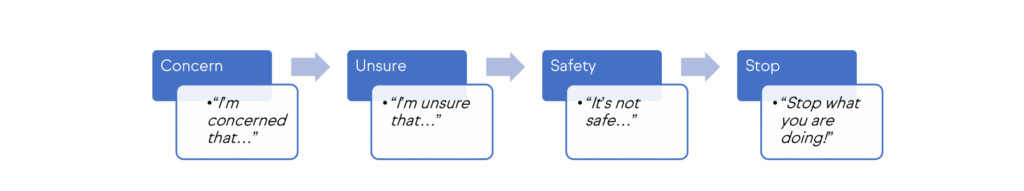

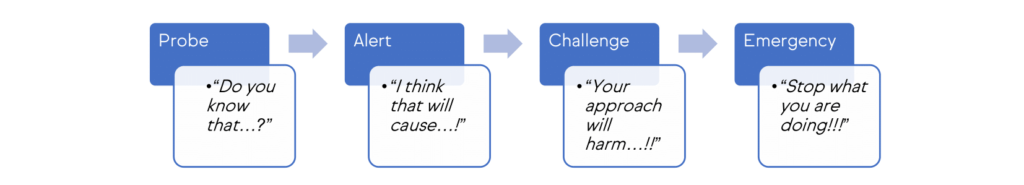

Frameworks to support graded assertiveness:

- CUSS (Concern, Uncertain/Uncomfortable, Safety and Stop) – a sequency that support communication when experiencing uncertainty or discomfort about a situation.

CUSS framework. Adapted from Speaking Up • LITFL Medical blog • MIME [Internet]. [cited 2022 Apr 29]. Available from: https://litfl.com/speaking-up/ - PACE (Probe, Alert, Challenge and Emergency) – the sequency starts with a question that intends to raise awareness to the problem in a subtle way (e.g. “Are you going to try to intubate again?”).

PACE framework Adapted from Speaking Up • LITFL Medical blog • MIME [Internet]. [cited 2022 Apr 29]. Available from: https://litfl.com/speaking-up/ - 5-step advocacy – An alternative approach:

5-step advocacy Adapted from Speaking Up • LITFL Medical blog • MIME [Internet]. [cited 2022 Apr 29]. Available from: https://litfl.com/speaking-up/

- Weller JM, Long JA. Creating a climate for speaking up. Br J Anaesth [Internet]. 2019;122(6):710–3. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2019.03.003

- Pian-Smith MCM, Simon R, Minehart RD, Podraza M, Rudolph J, Walzer T, et al. Teaching residents the two-challenge rule: A simulation-based approach to improve education and patient safety. Simul Healthc. 2009;4(2):84–91.

- Hanson J, Walsh S, Mason M, Wadsworth D, Framp A, Watson K. ‘Speaking up for safety’: A graded assertiveness intervention for first year nursing students in preparation for clinical placement: Thematic analysis. Nurse Educ Today [Internet]. 2020;84(September 2019):104252. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2019.104252

AdminKeymaster

AdminKeymasterThe term “speaking up” is used to refer to the assertive communication of quality and patient safety concerns by a team member through information, questions, or opinions in situations where a healthcare professional neglects, forgets or even ignores clinical guidelines to prevent patient harm.

Speaking up has a preventive effect on human errors and helps to improve system failures. But the research shows that sometimes those who speak up are ignored, and too often people choose to withhold their voice.1

- In a recent study in Austria, 32.3% of surveyed physicians and nurses said they had not expressed concerns regarding patient safety and 41.6% had kept ideas to themselves that could have improved patient safety in their unit.2

- An equivalent study with medical students revealed that 59% had not felt able to speak up in a critical situation. 3

- A study in Switzerland showed that an encouraging environment was related with higher speaking up frequency and lower withholding voice frequency. A poor climate, with high levels of resignation was associated with higher withholding voice.4

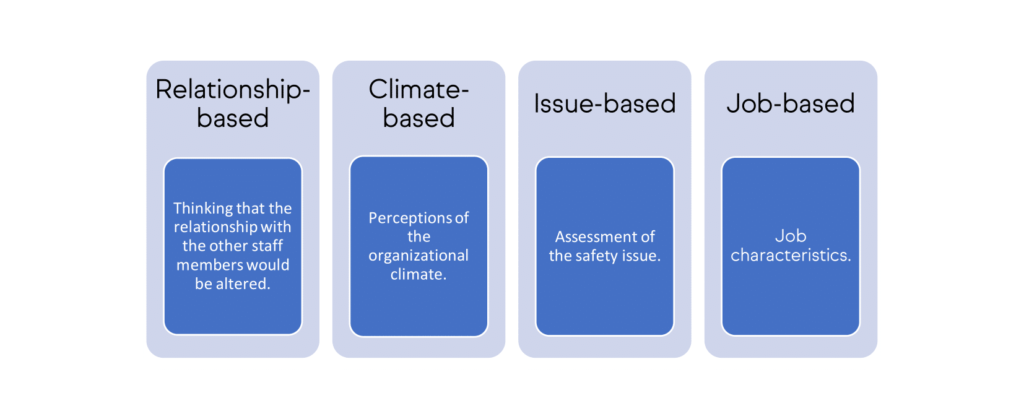

The work by Manapragada and Bruk-Lee5 identified four main motives behind silence about safety issues:

Reasons for staying silent about safety issues. Adapted from Manapragada A, Bruk-Lee V. Staying silent about safety issues: Conceptualizing and measuring safety silence motives. Accid Anal Prev. 2016;91:144–56 The study shows that safety motivation is not related with those motives (with the exception of issue-based, which would enable the recognition of the issue) suggesting that a highly motivated for patient safety worker will not be affected by those factors, so they won’t deter him from speaking up. This highlights the importance of an environment where the staff is highly motivated.

- Okuyama A, Wagner C, Bijnen B. Speaking up for patient safety by hospital-based health care professionals: a literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(61).

- Schwappach D, Sendlhofer G, Häsler L, Gombotz V, Leitgeb K, Hoffmann M, et al. Speaking up behaviors and safety climate in an Austrian university hospital. Int J Qual Heal Care. 2018;30(9):701–7.

- Schwappach D, Sendlhofer G, Kamolz LP, Köle W, Brunner G. Speaking up culture of medical students within an academic teaching hospital: Need of faculty working in patient safety. PLoS One. 2019;14(9):1–13.

- Schwappach D, Richard A. Speak up-related climate and its association with healthcare workers’ speaking up and withholding voice behaviours: A cross-sectional survey in Switzerland. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27(10):836–43. 5. Manapragada A, Bruk-Lee V. Staying silent about safety issues: Conceptualizing and measuring safety silence motives. Accid Anal Prev. 2016;91:144–56

AdminKeymaster

AdminKeymasterWithout an atmosphere where the workers feel confident to report the incidents and adverse events it is not possible to learn from the failures and to improve patient safety. To achieve this positive environment, it’s necessary a leaderships commitment and to take practical measures towards it, as education and training on Patient Safety.

But there are more difficulties to put in practice an effective learning system: the effort on collecting data creates a massive volume of information to examine, whereas the investment on analysing is many times proportionally small. The poor specification of what is to be reported and the data incompleteness are also, among others, weaknesses shown by previous studies. 1

The healthcare workers could feel personally discouraged to report incidents due to lack of time and lack of feedback from previous reports.

The WHO launched the Patient Safety Incident Reporting and Learning Systems – Technical report and guidance1 to support the establishment or reinforce the reporting mechanisms and to maximize the performance of learning from incidents. The document has also a self-assessment questionnaire that could be used by the organisations to evaluate their report system and to promote further discussion about strengths and improvements to take. Find in attachment:

1. World Health Organization. Patient Safety Incident Reporting and Learning Systems: technical report and guidance. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020

AdminKeymaster

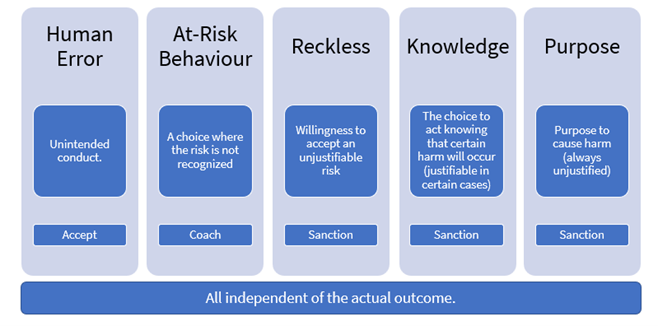

AdminKeymasterIt was already addressed that a culture of punishment and blame would undermine the objectives of Patient Safety because the hidden causes (the latent conditions) wouldn’t be addressed. For the other hand, one expects accountability from the healthcare sector when something bad occurs, and from the individuals who had a reckless behaviour or wilful misconduct. Recognizing that, just culture intends to develop a system where there is open reporting, but appropriate accountability of the individual’s actions.

Just culture is an environment which seeks to balance the need to learn from mistakes and the need to take disciplinary action. 1

It means that one has to distinguish between different behaviours that can result in harm, because they are qualitatively, technically and legally different. According to that, they might have differentiated consequences, as showed by Marx 2:

Just response to the 5 behaviours. Adapted from Marx D. Patient Safety and the Just Culture. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2019;46(2):239–45. Just culture intends to provide a productive discussion about system design and behavioural choices, creating also a safer psychological environment for the healthcare workers and promoting better outcomes to the patients.

- World Health Organization. The conceptual framework for the international classification for patient safety – final technical report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009.

- Marx D. Patient Safety and the Just Culture. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2019;46(2):239–45.

AdminKeymaster

AdminKeymasterWhen the incident is inappropriately managed and the communication is poor, it worsens the patient recovery, also increasing the likely of litigation processes.

The literature1 refers four main reasons for litigation:

- Explanation – the desire to find out how it happened but feeling ignored or neglected afterwards.

- Accountability – wish to see the professionals involved called to account.

- Standards of care – wish to prevent similar incidents in the future.

- Compensation – to receive a financial compensation.

However, the fear of litigation could lead to the practice of defensive medicine and to avoid disclosing incidents to patients.1 To break the cycle healthcare workers should be aware that open disclosure prevents litigation issues.

In the field of litigation, a study2 found that the relationship between malpractice litigation risk and the healthcare workers behaviours could be affected by many factors:

- the complexity of care provided – as it increases, the risk of an adverse increases and consequently the calls for accountability.

- the discussion of the incidents among the colleagues – it might encourage incident reporting and disclosure to patients.

- the personalized responsibility (in contrast with team responsibility where it is shared by team members) – is more likely to increase the impact of litigation risk on the behaviour of the individual who is responsible.

- the response of the organization to the staff after an incident – a non-punitive response to errors leads to an increase of the number of reports.

These factors are related with the organizational patient safety culture and psychological safety, which will be addressed in the next sections.

- Vincent C, Young M, Phillips A. Why do people sue doctors? a study of patients and relatives taking legal action. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1995;50(2):103–5.

- Renkema E, Broekhuis M, Ahaus K. Conditions that influence the impact of malpractice litigation risk on physicians’ behavior regarding patient safety. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):1–6.

-

AuthorPosts