From a blame culture to a systems approach

By the end of the twentieth century, the focus of incident analysis was on the events closely surrounding an adverse event, and on the human acts or omissions immediately preceding the event itself. This person-approach was a long-standing and widespread tradition and viewed unsafe acts as arising primarily from processes such as lack of memory, distraction, poor motivation, carelessness, or negligence.1 At that time, it was frequent to hear the term “medical error” to describe healthcare induced harm and a blame culture prevailed.

Today, it is well understood that a blame culture increases overuse and defensive practice and discourages the health care workers to disclose their errors and to talk about their patient safety concerns.

Furthermore, as evidence shows, in the great majority of cases the serious failures aren’t simply due to the actions of the individuals involved. Clinical errors are usually the end of a chain that has, in origin, a system or organizational failure that favours (and sometimes determines) that a frontline professional in the care of a patient commits a mistake that sometimes causes harm (adverse event). To punish an individual when the conditions of work are prone to the occurrence of errors seems inappropriate.

A systems approach focuses on the conditions under which people work and tries to build defences to avert errors or mitigate their effects. This approach recognizes that human errors, mistakes, and adverse events are inevitable and can’t be eliminated, but it’s impact could be reduced. Errors are seen as consequences rather than causes.1

Just because we accept that errors can happen does not mean that we allow them to happen without trying to avoid them. Precisely because we know that they occur, we have an obligation to detect the potential errors inherent in care activity in order to act accordingly. Not to do so is irresponsible and inadmissible.

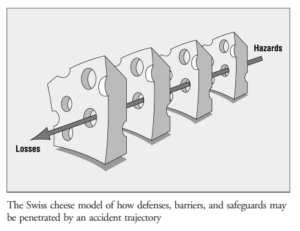

As explained by Reason’s cheese model, a high-reliable system has several layers of protection (the slices of the cheese). These defensive barriers can be engineered (e.g., alarms, automatic shutdowns), people (e.g., surgeons, anaesthetists) or procedures and administrative controls. They protect on most occasions but sometimes there are some holes, arising from two reasons: active failures and latent conditions.

Reason’s model. From Reason J. Human error: models and management. BMJ. 2000;320:768–70

The holes are constantly opening, closing, or realigning. Normally they don’t cause any bad outcome but when the holes in various defence layers are arranged in the same line, the trajectory of the accident occurs (as shown by the arrow).1

Active failures: ‘unsafe acts’ committed by those working at the sharp end of a system, which are usually short-lived and often unpredictable.

Latent conditions: Malfunctions of organization or design that can contribute to the occurrence of active failures. They can develop over time and lie dormant before combining with other factors or active failures to breach a system’s safety defences. They are long-lived and, unlike many active failures, can be identified and removed before they cause an adverse event. 1

Differentiating active failures and latent conditions allows the distinction of human contribution in the occurrence of accidents. Nevertheless, regularly the two sets of factors contribute to an adverse event. Contrasting from active failures, latent conditions can be identified and remedied before an adverse event occurs.1

Focusing on the system that allows harm to occur is the beginning of improvement. Anticipating the worst requires an organizational culture determined to make the system as robust as possible, instead of preventing isolated failures. It’s a work-in-progress that aims to know the root causes, why things go wrong. Although currently many organizations are focused on this pursuit, others are still taking the first steps.

Adverse events associated with an unwanted and avoidable outcome, such as those occurring in the case of chronic course processes, are clearly the most difficult to identify and prevent. Organizations that share an organizational culture that includes recognizing and talking about their failures and mistakes are the ones that manage to avoid them in the future. And this means creating an appropriate framework for doing so.

One technique that risk management teams have been using to respond to the questions “what happened?”,” why it happened” and “how to prevent that it happens again?” is Root Cause Analysis. Looking beyond human error, it aims to identify the system failures behind, and to implement appropriate changes. The goal is to prevent future errors thus improving Patient Safety.

Root Cause Analysis – “ systematic iterative process whereby the factors that contribute to an incident are identified by reconstructuring the sequence of events and repeatedly asking “why” until the underlying root causes (contributing factors or hazards) have been elucidated.”2

- Reason J. Human error: models and management. BMJ. 2000;320:768–70.

- World Health Organization. The conceptual framework for the international classification for patient safety – final technical report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009.

0 Comments